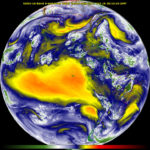

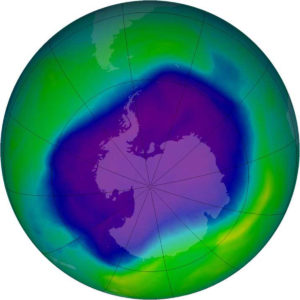

The ozone hole is a region where there is severe depletion of the layer of ozone — a form of oxygen — in the upper atmosphere that protects life on Earth by blocking the sun’s ultraviolet rays. (Photo credit: NASA)

Encouraging news arrived this week regarding the size of the Southern Hemisphere ozone hole. NASA reported that this year’s ozone hole (which peaked on Sept. 11 at 7.6 million square kilometers) was the smallest since 1988, just years after the problem was first identified.

Though a number of factors contribute to the annual size of the ozone hole, it is beyond doubt that the leading factor is the reduction of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), industrial chemicals long used for refrigeration among other things.

Just a few years after the ozone hole was detected via satellite, the industrialized nations of the world, meeting in Montreal in 1987, adopted what is known as the Montreal Protocol. That international agreement, based upon the consensus scientific understanding of the problem, placed prudent restrictions on the use of CFCs. The result of this scientifically informed policy-making has been a gradual but systematic healing of the ozone hole.

This should serve as a leading example of the power of scientific analysis and understanding to shape important environmental policy. The world is facing a slower burning crisis as a result of human-induced changes to the atmosphere that have, in turn, begun to change the climate.

There is no lack of scientific consensus of the roots of this problem nor any shortage of science-based prescriptions of seeking its remedy. The time has long passed for our society to seriously debate, and then begin to take, the bold actions necessary to meet this crisis. Our scientific and industrial infrastructure is more than sufficient to meet this pressing challenge — we have successfully done so before.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month.