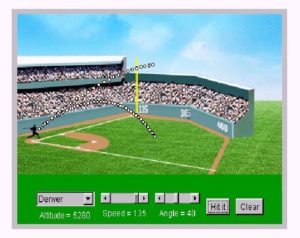

Explore physics involved in hitting a baseball

via the CIMSS Baseball WebApp at

http://cimss.ssec.wisc.edu/wxfest/FlyBalls/bb.html

We are now in the heart of the baseball season and even the casual fans begin to tune in a bit more regularly to the summer game. One of the long-standing pieces of baseball wisdom suggests that the heat and humidity of oppressive summer heat waves render the air “heavy” and lead to a decrease in offensive power, particularly in home runs.

The veracity of this “wisdom” is testable.

The air we breathe is a mixture of many gases (but mostly molecular nitrogen and oxygen). Since we know the constituents and their fractional amounts, it is fairly easy to determine the molecular weight of the mixture.

The most highly variable constituent of the mixture is water vapor, so it is useful to calculate the molecular weight of so-called “dry air” — air without any water vapor in it. That weight is 29.87 grams/mole. The molecular weight of water vapor (water as a gas) is only 18.02 grams/mole.

Consequently, when any amount of water vapor is mixed into dry air, the resulting mixture is less massive than the purely dry air. On the very humid days that attract our attention in the summer, this effect is at its height and the weight of the humid mixture is often much less than that of dry air. Sir Isaac Newton was the first to demonstrate this truth.

Thus, this piece of baseball “wisdom” is utterly false — it is much more likely that any decrease in power production observed during a mid-summer heat wave is a function of the human body’s inability to perform at its peak efficiency in the heat and humidity. It is definitely not because the air is “heavier.”