After a fairly prolonged stretch of warm and humid weather through mid-September, culminating in a temperature of 82 degrees just before midnight on Thursday, southern Wisconsin residents were greeted with low temperatures in the 40s on Saturday morning.

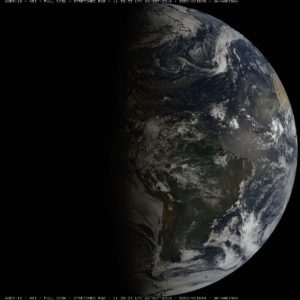

This seems particularly fitting as Saturday, Sept. 22, was the day of the autumnal equinox this year — fall officially arrived at 8:54 p.m. that night.

In the past three months, we have lost over 3 hours of daylight and over the next three we will lose an additional 3 hours.

The situation is even worse at higher latitudes. At the North Pole, for instance, the sun dipped below the horizon Saturday night for the first time in six months and will not be seen again for six more months.

The polar darkness will now begin its inevitable creep southward, reaching 66 degrees 30 minutes latitude just before Christmas Day.

Thus, a gradually expanding area of the Northern Hemisphere will be plunged into daylong darkness with each passing day. In the absence of any sunlight, the air in these locations will be subject to uninterrupted radiational cooling, which will lead to the production of very cold air masses.

The cold air will continue to advance southward across the hemisphere through about the last week of January when it will begin its slow retreat back toward the pole as winter begins to lessen its grip.

So, as we all enjoy these first few days of fall, their magnificence comes with a hidden, lurking price and the bill will come due in December, January and February.