Tornadoes are sometimes not seen and thus sometimes not counted. Particularly early in the record keeping.

But scientists interested in this question have studied the change in the key ingredients that form tornadoes, such as wind shear, atmospheric stability and humidity. The more often those ingredients are present, the more likely tornadoes are to form.

So, a recent study counted the number of tornado reports between 1979 and 2016 and also tracked the conditions favorable for tornado formation. They found that increases in the ingredients were reflected in a larger number of tornadoes.

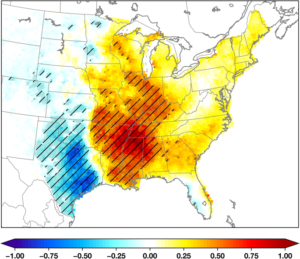

The study found that since 1979, some places have seen increases in tornadoes and other regions showed a decreasing trend. Tornadoes are decreasing in Oklahoma, Texas and Kansas but are increasing in states along the Mississippi River and farther east, including Wisconsin.

The Great Plains have seen a slight decrease, with the biggest change in central and eastern Texas; however, Texas still has the most tornadoes of any state. The west coast of Florida is the only place east of the Mississippi that didn’t show an increase.

While tornado alley — Oklahoma, Colorado and central and eastern Texas — has the most tornadoes, the states with the deadliest tornadoes are Alabama, Missouri, Tennessee and Arkansas.

Scientists aren’t sure of why the eastward shift has been observed. It could be dry conditions in the plains moving farther eastward.

Why does this matter? The shift eastward means that more people and homes are exposed to a tornado threat.