Temperature is a fundamental indicator of a climate. Annual and seasonal temperatures patterns have a defining role in the types of animals and plants that reside in an ecosystem. Rapid changes in temperature can disrupt a wide range of natural processes. This is one reason we monitor temperature changes as a metric for global change. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information maintain a collection of climate data online at: www.ncei.noaa.gov

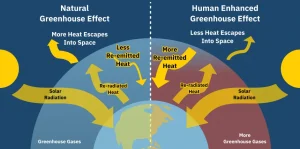

Concentrations of heat-trapping greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, are increasing in the Earth’s atmosphere. This increase is due to anthropogenic activity. In response, the average temperatures at the Earth’s surface are increasing and are expected to continue rising. Though global temperature changes can shift the wind patterns and ocean currents, the regional warming is not uniform.

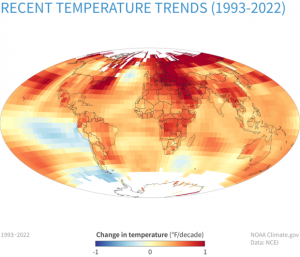

The observed global average surface temperature has risen at an average rate of 0.17°F per decade since 1901. Since 1901, the average surface temperature across our contiguous 48 states has similarly risen at an average rate of 0.17°F per decade. The average temperatures have risen more quickly since the late 1970s: from 0.32 to 0.51°F per decade since 1979. For the contiguous United States, nine of the 10 warmest years on record have occurred since 1998.

The changes across the globe show no uniform patterns in the rate of increase. The temperatures of the Arctic are rising two to four times faster than the global average. The Antarctic Peninsula has also experienced a similarly dramatic warming. Desert areas also warmed at rates exceeding the global average warming rate.

Of course, this regional variability makes the problem of accurately predicting how the associated changes in weather patterns across the globe will change in a warmer world even more difficult to solve. However, understanding such weather variability is absolutely critical to meeting the warmer future with in the least disruptive way.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at noon the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.