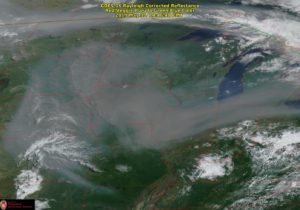

There have been large forest fires in northern Alberta, Canada, and the smoke has drifted over the Midwest, including Wisconsin.

Smoke can cause the sky to appear hazy, even if the smoke is high above the ground. The smoke scatters sunlight to make the sunlight diffuse and grayish. When the smoke is thick, it can cause brilliant red sunsets and sunrises, as it did on Thursday. When light beams interact with particles suspended in air, the light can be scattered or absorbed.

The amount of light that is being scattered is a function of the number of particles and the size of the particle relative to the wavelength of the light falling on the particle. Small particles, like those of which smoke is composed, scatter violet and blue light more effectively than other colors.

So, as the sun sets and its rays pass through the smoke plume, all the blue light is scattered out of the path between the setting sun and your eyes, leaving just the red and orange colors. This results in the sun having a bright red color when it is low on the horizon. Recently, the smoke above us has been thick enough that the red sun disappeared from view before it set below the horizon.

Winds will sometimes transport the smoke down to the ground, resulting in a reduction in the quality of the air we breath. The small particles that make up the smoke can cause respiratory problems, particularly for children, the elderly and people with asthma.

Smoke doesn’t have much of an effect on our temperature or precipitation. However, official weather reports include observations on sky conditions and visibility.