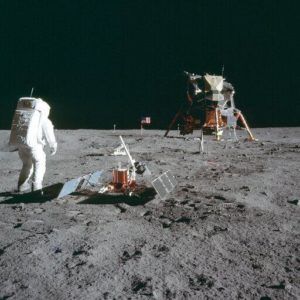

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin Jr. stands next to the Passive Seismic Experiment device on the surface of the moon on July 20, 1969, during the Apollo 11 mission. The space race was responsible for enormous advances in satellite technology. (Photo credit: Neil Armstrong)

On Saturday, we will mark the 50th anniversary of humankind’s first-ever footsteps on a different world, the lunar landing of Apollo 11.

The moon landing represented the peak of the Cold War’s space race and, though motivated by martial competition between geopolitical adversaries, the drive to reach the moon produced a large number of technical advances which most of us take for granted today.

With specific respect to weather forecasting, the space race was responsible for enormous advances in satellite technology that now provide the backbone of the global observations of the atmosphere required to power the weather prediction enterprise.

Another extremely important aspect of the prediction revolution was the rapid development of computer technology. Despite the fact that your mobile phone has more computing power than the entire array of machines available to Mission Control in July 1969, the Apollo program drove the development of smaller and more powerful computers.

Finally, the Apollo program provided inspiration to thousands of young boys and girls who were fortunate enough to see, at an early age, what science really is — a grand adventure of exploration and discovery. One of us (Martin), still retains vivid memories of making the first footprints in the newly fallen snow of a New England blizzard while delivering morning newspapers and imagining himself as Neil Armstrong. That sense of kinship with a hero of exploration likely fueled more than one young person’s desire to pursue the wonders of science.