The Farmers’ Almanac recently published its 2020-2021 winter forecast. For the Midwest region, it predicts a cold winter with normal to below-normal temperatures.

But don’t count on its forecast, as there is no proven skill. The Farmers’ Almanac does not share how it makes its forecast, so it cannot be judged scientifically.

The Farmers’ Almanac also makes a weather forecast for specific time periods in a given season. Such detailed forecasts can be announced but are not trustworthy scientifically.

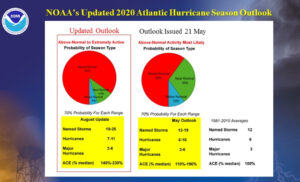

Seasonal weather forecasting is a science challenge. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center (CPC) also makes seasonal forecasts. It explains the underlying principles of its forecast and provides validation of its forecasts publicly (see www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/long_range/tools/briefing/seas_veri.grid.php).

These modern-day seasonal forecasts rely on known relationships between climate and some key forcing mechanisms, such as the El Niño. An El Niño is a periodic warming of the equatorial Pacific Ocean between South America and the Date Line. This warming is a natural variation of the ocean and is used to predict departures from average conditions rather than to make specific weather forecasts. For example, a year with a strong El Niño leads to less snow fall than average in Wisconsin. These seasonal forecasts also take into account the climatic impacts of other global oscillations uncovered by the research of atmospheric scientists.

There is about a 60% chance of a La Niña, a cooling of the equatorial Pacific Ocean between South America and the Date Line, developing during the Northern Hemisphere fall and continuing through winter 2020-21. This will influence global weather patterns. The CPC predicts there is an equal chance our wintertime temperatures will be above, below, or at average conditions. They are also calling for a 40% to 50% chance that our winter precipitation will be above normal.