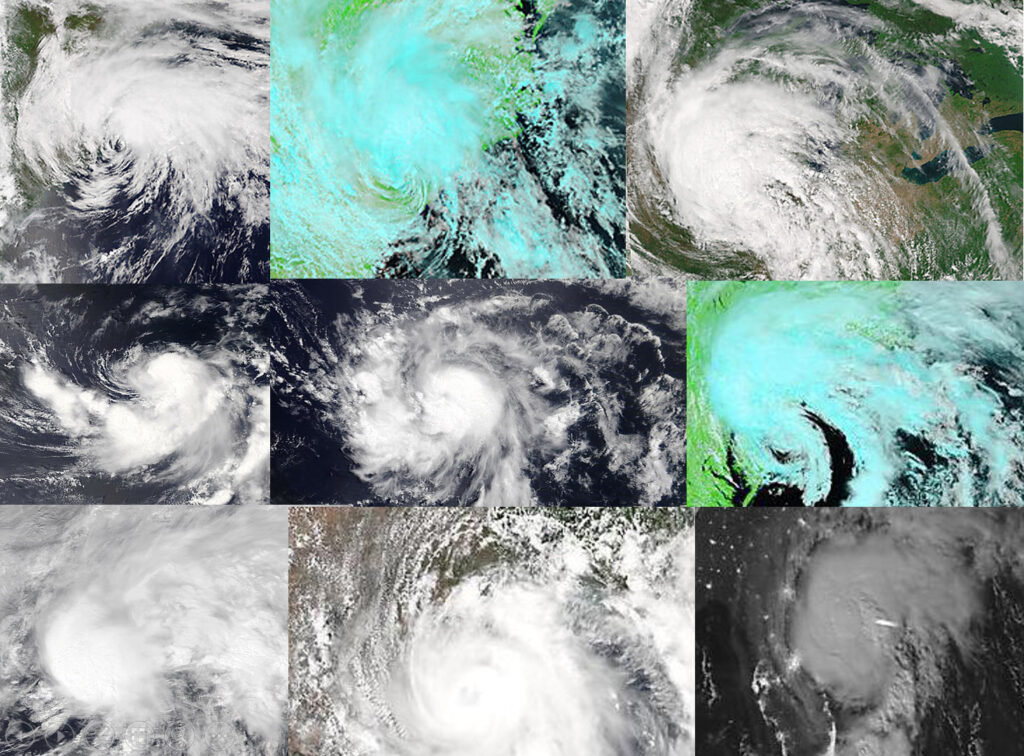

When Hurricane Laura made landfall just south of Lake Charles, Louisiana, at 2 a.m. Thursday, it did so as the strongest hurricane to strike the state in more than 160 years and one of the top 10 strongest landfalling storms in U.S. history.

By the time the storm came ashore 30 miles south of Lake Charles, it likely packed gusts to over 150 mph. Indeed, the peak gust at Lake Charles was 137 mph — truly incredible considering that the city is 30 miles from the coastline.

Even though the storm hit a rather less populated part of the Gulf Coast, nearly 1.5 million people were involved in some sort of evacuation and more than 900,000 lost power. The storm surge was between 12 and 21 feet, and some locations received more than 18 inches of rain.

Despite these manifestations of Laura’s destructive potential, thus far only 14 people have died from the storm and several of those were victims of carbon monoxide poisoning, not the weather/flooding itself. The remarkably low death toll is almost surely a result of the extremely accurate forecast for this storm’s location and time of arrival.

Click on image for an animation

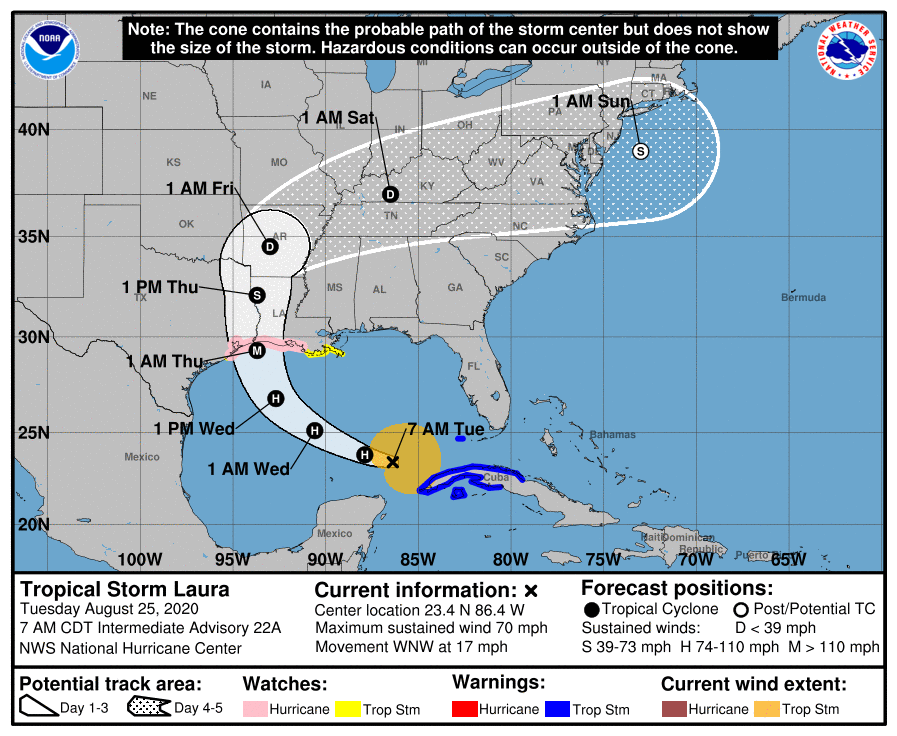

While Laura was still getting organized over Haiti, some 87 hours before it made landfall, the National Hurricane Center predicted the time of landfall precisely and the location to within 0.6 miles (the equivalent of sinking a 900 foot putt). The intensity was underforecast as a result of the unexpectedly rapid intensification in the last 24 hours before it crashed ashore. The peak winds increased by 65 mph in that interval.

Nonetheless, in the post-storm analysis that is now ongoing, the exceptional timing and placement forecasts will undoubtedly rise to the top of the list of reasons why this powerful storm did not take more lives.