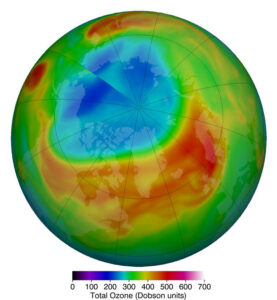

The ozone hole refers to the appearance of very low values of ozone in the stratosphere.

The winter atmosphere above Antarctica is very cold. It occurs typically high over the continent of Antarctica, during the Southern Hemisphere’s spring. The cold temperatures result in a temperature gradient between the South Pole and the Southern Hemisphere middle latitudes, which results in strong westerly stratospheric winds that encircle the South Pole region.

These strong winds, called the Polar Vortex, prevent warm air from the equator from reaching these polar latitudes. These extremely cold temperatures inside the strong winds help to form unique types of clouds called Polar Stratospheric Clouds, or PSC. PSCs begin to form during June, which is wintertime at the South Pole.

Chemicals on the surface of the particles composing PSCs result in chemical reactions that remove the chlorine from the atmospheric compounds. When the Sun returns to the Antarctic stratosphere in the spring (our fall), sunlight splits the chlorine molecules into highly reactive chlorine atoms that rapidly deplete ozone. The depletion is so rapid that it has been termed a “hole in the ozone layer.”

An Arctic ozone hole is rare, but one did develop this spring. The winter of 2019-20 was unusual. The cold temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere polar region were present all winter long without ‘weather’ disrupting the circulation pattern.

PSC were abundant throughout the dark winter months, creating a larger reservoir of reactive chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) byproducts than usual. As the Sun returned through late February and early March, destruction of ozone over the Arctic occurred rapidly. The 2020 Artic ozone hole came to an end on April 23.

Satellite observations routinely measure ozone across the planet. The lowest ozone values over the Arctic are less severe than the hole that forms every year over Antarctica.