Today is March 1 so the meteorological winter (December-January-February) is over.

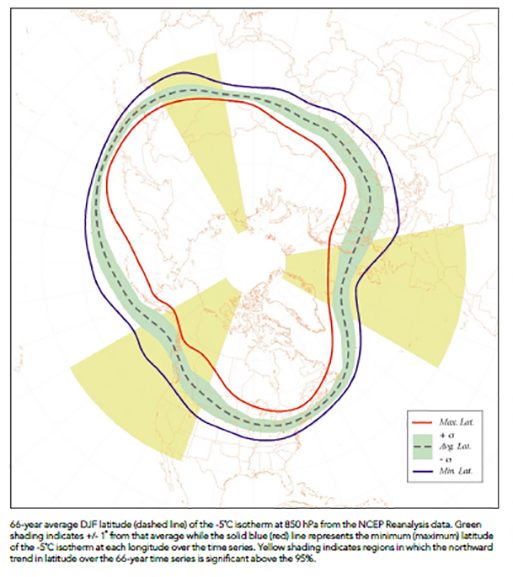

The areal extent of air colder than minus 23 degrees at about 1 mile above the ground throughout December through February is one way of comparing the severity of the Northern Hemisphere winter from one year to the next.

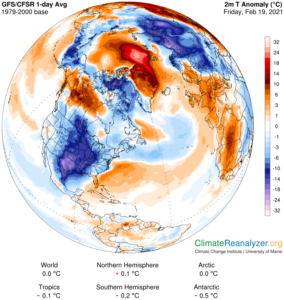

Using the National Center for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) reanalysis data set we have been able to make such a calculation for each winter season since 1948-49. Despite the severe cold snap experienced over much of North America in the middle of February this year, the seasonal average cold pool area over the entire hemisphere was the ninth smallest in the last 73 years. This is consistent with a systematic shrinking of the wintertime cold pool extent that has seen the average seasonal area decrease by nearly 5% since 1948.

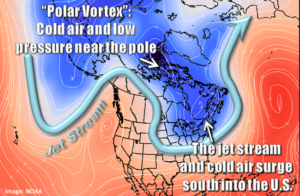

This shrinkage is, of course, at the southern edge of the cold pool and is not a function of changes in weather systems that parade around the globe on that edge. Instead, it is a result of increased retention of infrared radiation emitted by the surface of the Earth which is intercepted primarily by the increased concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The monthly average carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere for January 2021, the last month for which averaged values were available, was 415.52 parts per million (ppm). That compares to 354.93 ppm just 30 years ago and 316.89 ppm 60 years ago. This means that the rate of increase has more than doubled in the past 30 years.

The shrinking of the wintertime cold pool is a predictable result of this increase — an increase that lies behind the unmistakable global warming that continues to alter the climate.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month