As the threat of winter snows recedes across the country, it is replaced by the threat of severe weather (i.e. thunderstorms with hail, damaging winds and tornadoes).

The severe weather season, though broadly spanning March through August across the United States, is actually quite regional. It begins in March in the southern states, moves to the southern Plains during April and May, and then further north toward the Great Lakes states during the summer.

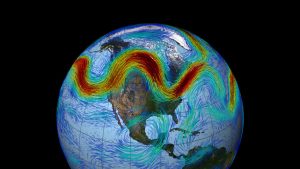

One of the basic underlying reasons for this northward migration of the severe weather threat during the spring and summer is the fact that the jet stream follows a similar seasonal cycle.

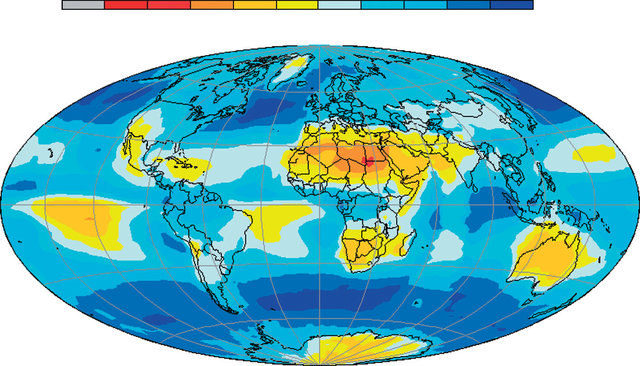

The jet stream is a ribbon of high wind speeds located near the top of the troposphere, about 6 miles above the surface of the Earth. The jet stream position is anchored to the southern edge of the dome of cold air that is centered on the North Pole. During the depths of winter, that cold dome expands considerably, extending nearly to the Gulf of Mexico. As the winter ends and spring approaches, the hemisphere begins to warm up and the cold dome shrinks dramatically. Its southern edge moves to central Canada by early summer.

The jet stream is associated with vigorous vertical circulations — upward and downward motions. The upward vertical motions are instrumental in producing thunderstorms. Thus, when the jet stream migrates northward as the weather warms in spring and summer, so does the greatest concentration of severe weather outbreaks.

This very sort of situation characterized the severe outbreak last weekend in several southern states.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at noon the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.