The latest frost in spring is important to gardeners as we seek to protect our garden plants from freezing temperatures. For Madison, based on temperature observations between 1940 and 2024, the latest frost occurred on 10 June 1972 and the earliest final frost occurred on 7 April 1955. The last frost date varies from year to year as it is strongly dependent on current weather conditions. To best estimate the last frost is to use statistics over a given time period. The median date for the last frost in Madison is May 5. Giving the median date of last frost means that there is still a 50% chance that a frost will occur after this date.

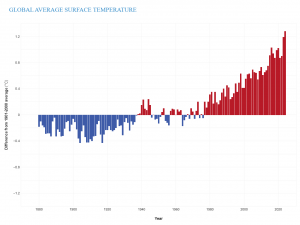

An analysis of Madison’s last frost date from 1940 – 2024 shows a trend consistent with the scientific expectations of global warming, that the last frost date now occurs earlier in the spring. Our nighttime minimum temperatures have been getting warmer and that too is consistent with the last frost date moving earlier.

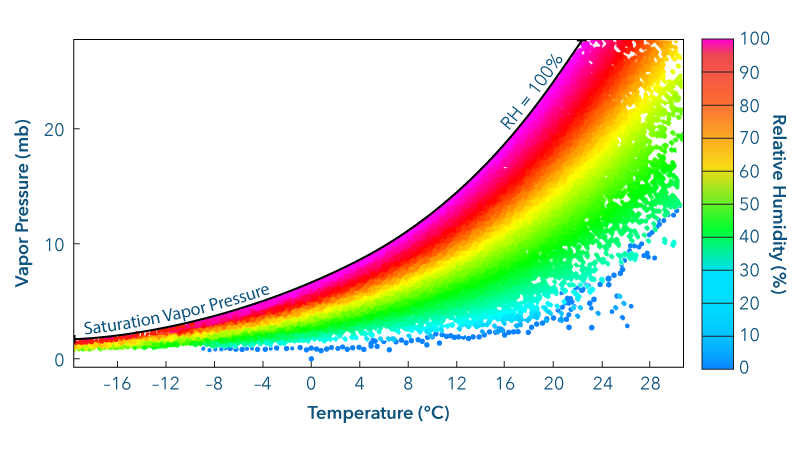

In addition to following local forecasts, there are some observations you can make to aid in predicting the formation of frost in your yard. If at sunset the temperature is close to freezing, then there is a better chance for the formation of frost overnight. Clouds are good emitters of infrared energy so they reduce the energy losses at the ground during the night. If it is cloudy and will stay cloudy, then the likelihood of frost is reduced. Knowing the dewpoint is also important. A rule of thumb–if the dew point is above 45°F at sunset then you are probably OK. If below 40°F, you will probably see a frost if the other weather conditions are aligned.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at noon the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.