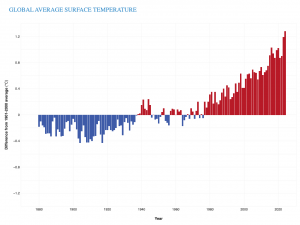

Global warming refers to the recent rise in Earth’s average temperature caused by human activities that emit higher levels of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane. Scientists understand the physics and chemistry of how these gases warm the atmosphere.

The global average temperature has increased about 1.7°F since 1970. During this same period, temperatures have risen around 2.5°F in the contiguous United States and 4.2°F in Alaska. The 10-year period 2014–2023 was the warmest decade on record. Such warming has, of course, altered average weather conditions, including temperature, precipitation, humidity, wind patterns, atmospheric pressure, and ocean temperatures and so global warming is nearly synonymous with climate change. Although it is difficult to directly attribute specific weather events to global warming/climate change, data analysis indicates that global warming is linked to more extreme weather events such as droughts and floods. There has also been an increase in days with temperatures above 90°F and heat waves. Heat waves, defined as periods of unusually hot weather lasting two or more days, have become more frequent in major cities across the United States, rising from an average of two heat waves per year in the 1960s to over six per year in the 2020s.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (their synthesis report was published in March 2023), represents the work of hundreds of leading experts in climate science. That report states, “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere, and biosphere have occurred.”

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at noon the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.