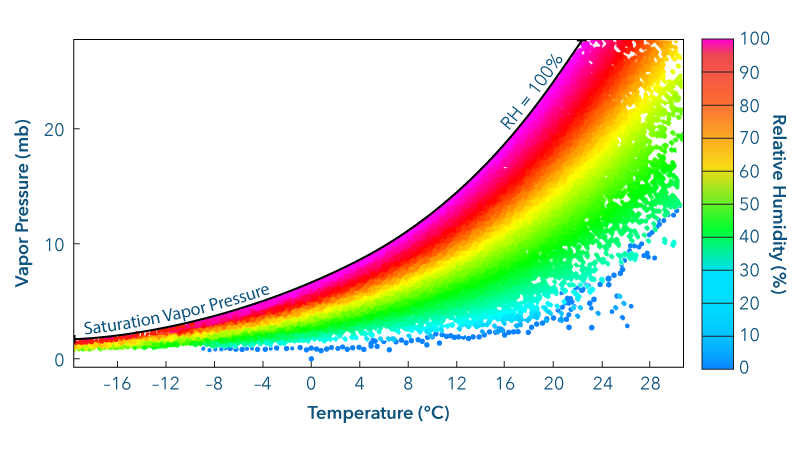

Weather reports often include the dew point temperature and the relative humidity. These are just two of several ways to express the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere. Vapor pressure is another way. Each method has advantages and disadvantages.

Gas molecules exert a pressure when they collide with objects. The atmosphere is a mixture of gas molecules and each type of gas makes up a part of the total atmospheric pressure. The pressure the water molecules exert is another useful method of representing the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere. The pressure caused by these water vapor molecules is called the vapor pressure. Atmospheric vapor pressure is expressed in millibars (mb).

Water vapor is at most only 4% of the total atmosphere. The average surface pressure as a result of all atmospheric gases is approximately 1,000 mb. Therefore, the vapor pressure attributable to water vapor alone is never more than about 4% of 1,000 mb, or 40 mb.

A variety of factors can change the vapor pressure. Increasing the air temperature will increase the vapor pressure. Changing the air temperature changes the average kinetic energy of the molecules and, therefore, the pressure exerted by the molecules. Increasing the number of water vapor molecules in a specific volume of air will also raise the vapor pressure. Therefore, when water evaporates into a volume of air, the vapor pressure increases.

The ratio of the actual vapor pressure exerted by molecules of water vapor versus the saturation vapor pressure at the same temperature indicates just how close the air is to saturation. This ratio is called the saturation ratio. Multiplying the saturation ratio by 100% yields the relative humidity.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at noon the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.