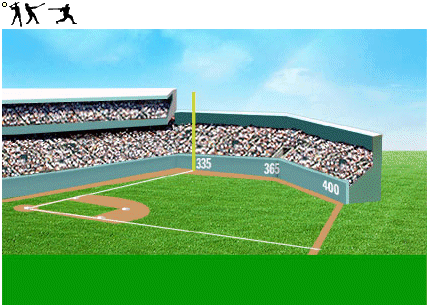

As the baseball season reaches its annual All-Star break, perhaps you have noticed (as we have) that baseball broadcasters are beginning to refer to “heavy” air as the summer reaches its peak.

This “heaviness” is sometimes offered as a warning to fans that they should not expect a lot of home runs on a given night.

The fact that high humidity in the summer can sap one’s energy is a familiar physiological reality for almost all of us, and so it almost certainly has a bearing on athletic performance. This impact, however, has nothing to do with the weight of the air that surrounds us.

As it turns out, the exact opposite is actually true. Even if the air were perfectly absent of water vapor, the warmer that air gets the less dense it gets. This means the air is lighter as it warms up.

In fact, anyone who has thought about why a hot-air balloon works is likely to have come to this conclusion at some point.

If we add water vapor to the air, which is common in summer and accounts for the uncomfortable feel of a muggy day, the air gets even lighter. That is because humid air is a mixture of “dry” air and invisible water vapor. Since the dry air has a molecular weight of about 29 grams/mole (1.29 grams/liter) and water vapor has a molecular weight of about 18 grams/mole (0.804 grams/liter), any mixture of dry air and water vapor drops the weight of air below what it would be were it completely void of water vapor.

Thus, the broadcaster’s suggestion that summer air is “heavy” is physically incorrect.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month.