We are in the midst of another hot spell here in southern Wisconsin.

Last Friday was the first of several days that were forecast to see high temperatures at or above 90 degrees (we’ve had only six through Friday all season!).

The high on Friday only reached 88 as the sky was a bit more obscured than was forecasted.

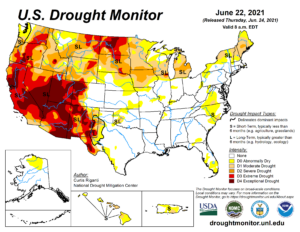

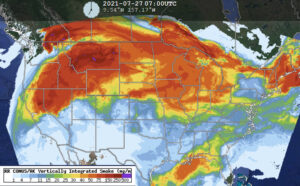

The obscuring factor was a combination of high cirrus clouds and smoke from the Western wildfires. The first of those factors, high cirrus clouds, is a common summertime suppressor of the high temperature.

Their exact location, timing and duration are very hard to predict accurately and so they are often the primary reason why a given summer day’s high temperature forecast might be too high.

Despite the difficulty of forecasting high clouds, the numerical models used by the National Center for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) are designed to simulate their development through the routine inclusion of humidity, wind and temperature data in the models.

The other factor conspiring to lessen the heat on these several days, wildfire smoke, is not well accounted for in those same models.

Because such large-scale smoke plumes are only episodic it is much more difficult to confidently account for their presence in these forecast models.

Smoke definitely reduces the amount of sunlight that is absorbed at the ground and so conspires to keep the temperature a bit cooler than it might have been in the absence of the smoke.

So, if the forecasted high temperatures over the weekend and early this week seem to be systematically a bit too high, it might well be a direct result of the wildfires that are raging in the Western states.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.