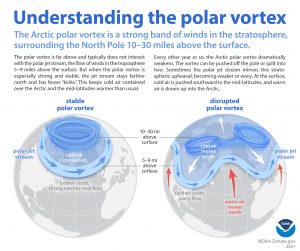

The polar vortex is a large area of low pressure in the lower stratosphere that is bordered on its southern edge by the polar night jet — so-called because it develops as the sun sets at high latitudes after the autumnal equinox, creating large and deep pools of cold air. The characteristics of this stratospheric polar vortex have a substantial influence on wintertime temperatures in the lowest part of the underlying troposphere, which is where we all live.

The nature of the polar vortex changes throughout the winter. When the vortex circulation is largely west-to-east around the pole, it tends to contain the most extreme cold air masses at high latitudes. When it is characterized by high amplitude waves, often associated with a weaker vortex, it can initiate rapid transport of warm air poleward in some locations and frigid air equatorward in others. Such waves, or lobes, of the polar vortex can pinwheel over the Northern Hemisphere, sending cold air southward in association with weather systems tied to the underlying tropospheric jet stream.

Our global climate is warming because of human activity. Near-surface Arctic temperatures are rising more than twice as fast as those at lower latitudes because of the retreat of snow and ice, which reduces the amount of reflected solar radiation at high latitudes. This is known as “Arctic amplification,” and it reduces the mid-tropospheric temperature contrasts that support a strong, circular polar vortex.

Some research suggests a weaker temperature gradient allows the jet stream to meander more easily, promoting the kind of wave amplification that disrupts the polar vortex. If so, this would indirectly increase the likelihood of a midwinter polar vortex sending cold air south.

So, while global warming is reducing average cold temperatures overall, disturbances in the high-latitude circulation can still create sharp, temporary cold air outbreaks.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at noon the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.