Storm systems that form in middle or high latitudes, in regions of large temperature contrast are called extratropical cyclones. This contrasts with tropical cyclones, such as hurricanes, which form in regions or relatively uniform temperatures.

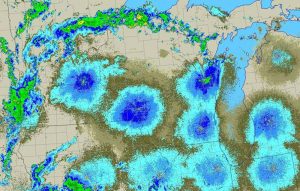

Extratropical cyclones are surface low-pressure systems where the air at the surface flows counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere and clockwise in the southern hemisphere. The winds around these centers of low-pressure spiral inward at the surface, forcing rising motions. The rising air can result in clouds and precipitation. The process of extratropical cyclone development and intensification is referred to as cyclogenesis. In North America there are favorable regions for cyclogenesis, including the eastern slopes of mountain ranges, the Atlantic Ocean off the Carolina Coast, and the Gulf of Mexico. The jet stream also influences cyclogenesis.

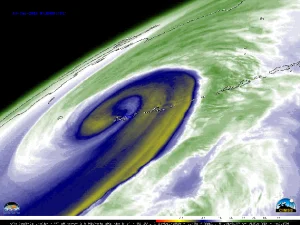

The polar jet stream is a zone of faster moving air in the upper troposphere. Its meandering pattern has regions of convergence and divergence. The position of the jet stream influences cyclogenesis. To maintain a low pressure at the surface, the rising air associated with the surface convergence, must transported away at the top of the developing storm. The upper air divergence associated with a jet stream maintains the low pressure at the surface, by removing air from the column, reducing its weight and causing the pressure to fall at the surface.

During cyclogenesis the surface pressure in the storm is decreasing. How fast the surface pressure decreases is an indication of how the storm is developing.

A ‘meteorological bomb’ is an unofficial term for very rapid, or explosive, cyclogenesis. It is defined as when the central pressure of a developing extratropical cyclone falls 24 millibars in 24 hours.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at noon the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.