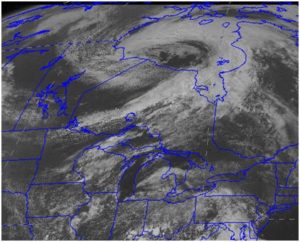

This classic comma shaped cloud, also called a mid-latitude cyclone, deepened over Hudson Bay Canada during mid-August 2016.

(credit: Steve Ackerman, CIMSS)

As we head into the second half of August a subtle transition in our weather begins to occur — one that is probably hard to detect at first but that eventually becomes very obvious and then lasts for approximately eight months.

We are not talking about the gradual reduction in daytime high temperatures or the increasingly cooler to cold nights, though these are also beginning to invade.

Instead, we are talking about the nature of the storms that deliver our precipitation.

Throughout the summer, most of our precipitation comes in the form of thunderstorms, wherein large amounts of precipitation fall in a short amount of time from what we call convective clouds.

Most often these storms have life cycles of only a few hours and drop precipitation over a relatively small area.

These characteristics also make the exact timing and location of summertime precipitation difficult to forecast.

As we transition to late summer/early autumn, the thunderstorm frequency abruptly decreases and precipitation tends to occur in persistent, light to moderate rain events that will sometimes last an entire day.

This mode of precipitation is associated with the passage of what are known as mid-latitude cyclones — storms that live for over a week, during which time they can cover an area the size of 10 states and characteristically take on a comma-shaped appearance in satellite imagery.

As they progress across the country, these mid-latitude cyclones can drop precipitation (rain or snow) over enormous portions of the country.

Though not entirely missing from summertime precipitation, such events are definitely the exception rather than the rule in the summer.

This past week, the first really well developed such storm of the season paraded across Hudson’s Bay in Canada and another one like it is poised to do the same late this week.