The summer solstice marks the longest day of the year.

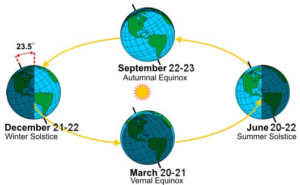

It is an astronomical event caused by Earth’s tilt on its axis and its orbit around the sun.

Monuments such as Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, demonstrate that ancient cultures knew the path the sun traveled through our sky changed in a routine way throughout the year. They undoubtedly observed that how high the sun appears in the sky varied throughout the year and that the higher the sun gets in the sky, the longer the length of daylight.

Our summer solstice occurs when the sun is directly overhead at noon at 23.5 degrees north of the equator, the latitude called the Tropic of Cancer. This is the farthest north the sun ever gets. This year, the sun reached the Tropic of Cancer at 10:32 p.m. Sunday.

At the summer solstice, the sun reaches its highest point in the sky and daylight is longest. The sun rises and sets farthest north at the June solstice. However, our earliest sunrise occurred on June 14, while our latest sunset occurs about a week later than the summer solstice. So, while the summer solstice has the longest daylight hours, that day does not correspond to the earliest sunrise or the latest sunset.

The time when the sun reaches its highest point in the sky is called solar noon. Solar noon rarely occurs exactly at clock noon — it’s sometimes before and sometimes after noon on our clocks. In June, the day, as measured by successive solar noon, is nearly 1/4-minute longer than 24 hours. Hence, the midday sun, when the sun reaches its highest point in the sky, comes later by the clock on the June solstice than it does one week before. Therefore, the sunrise and sunset times also come later by our clock.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.