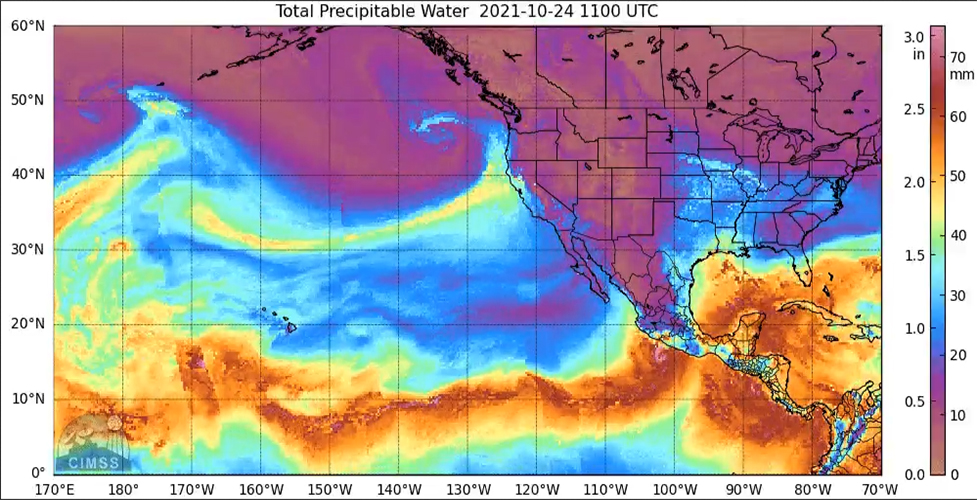

On Nov. 7, numerous “holes” appeared to be punched out of a cloud deck across the Upper Midwest.

Punch holes can occur after a plane flies through the cloud if the cloud droplets are supercooled, with their temperatures below freezing.

A plane flying through a cloud can cause some droplets to freeze. The presence of both liquid water and ice crystal in a cloud yields a unique precipitation-making ability. The water evaporates from the supercooled droplets and flows toward and deposits on the ice crystals. This process is called the Bergeron-Wegener process. It was first proposed by Alfred Wegener in 1911 and explained more extensively by Tor Bergeron.

You can see the ice crystals falling out of the cloud in the accompanying photo, resulting in a cloud-free circle.

There is a difference between freezing a small water droplet and freezing a larger body of water. The freezing temperature of water is 32 degrees at standard pressure. That is the case when water is in dish, ice tray or lake. A 1-millimeter diameter droplet will generally not freeze until the temperature falls below 12.2 degrees. A tiny droplet, but not a large body of water, can be supercooled.

(Image credit: CIMSS Satellite Blog)

For ice to form, all the water molecules must align in the proper crystal structure. First, a few molecules align, and then the rest quickly follow, turning the liquid into a block of ice. The larger the volume of water, the greater the chances that a few of the molecules will align in the proper manner to form ice when the temperature falls below freezing. In a small volume of water, the chance that some of the molecules will align in the correct structure is reduced, simply because there are fewer molecules.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.