We will not see 80 degrees again this year.

The last time Madison was officially 80 degrees or warmer was Sept. 21, the last official day of summer. In fact, 13 of the first 21 days of last month we were at least that warm — fairly remarkable.

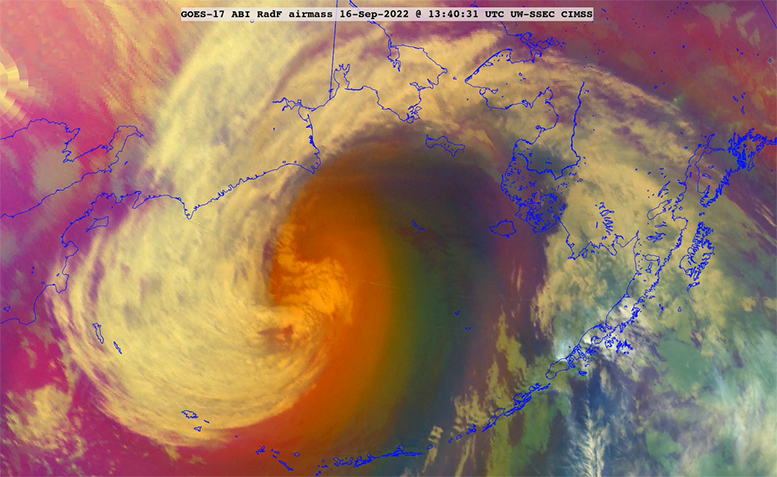

The weather has turned abruptly since then, culminating with our first really cold air of the year from Thursday night into Saturday. A number of locations in the area had their first night below freezing during this stretch, and temperatures dropped to 12 degrees in a couple of towns in southwestern North Dakota.

The dramatic about-face got us thinking about that 80-degree mark and whether it is likely to appear again this year.

The earliest day on which Madison has ever recorded its last 80-degree day of the year was Sept. 2, 1977 (and 2020). The all-time latest 80-degree day in Madison’s history was on Oct. 23, 1963. The average last such day (since 1939) is Sept. 29.

Within the 83 seasons (not including this one) since 1939 there have been 17 times when the last 80-degree day occurred after today’s date, Oct. 10 — just over 20% of the time. Though that might inspire hope that it is not terribly unusual to get that warm after today’s date, this year it seems unlikely that we will see that kind of warmth again as at least the next 10 days seem certain to be cooler than that.

So, enjoy the brilliant sunshine, light winds and dry conditions that have set in over us these last couple of weeks — but consider the summer officially over.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.