It is a fair bet that we would get near universal agreement that this October has been pretty spectacular here in southern Wisconsin.

Through the 29th, the average temperature has been exactly normal, and we have had only 11 days on which precipitation fell — twice it was snow — for a total that is 1.75 inches below normal.

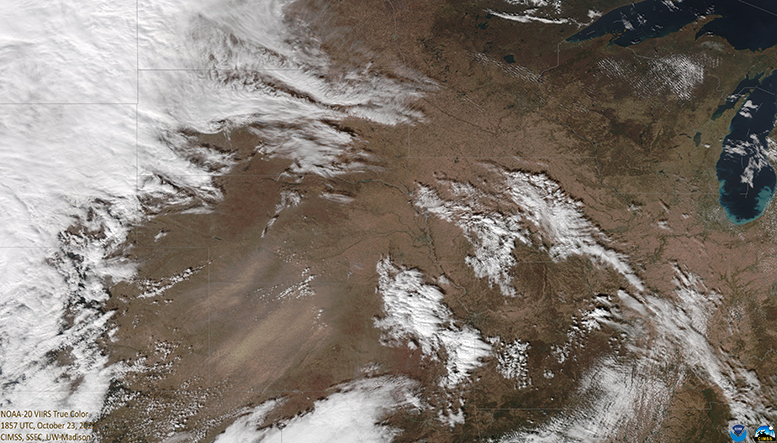

Oct. 21 began a streak of four consecutive days with a high temperature of 72 degrees or higher, with the warmth soaring to 76 and 77 on the 21st and 22nd. Amazingly, this is just the third such streak that has ended as late in October in Madison’s 150-plus years of weather records.

Previous streaks ending this late in the month ran five days and occurred Oct. 23-27, 1989, and Oct. 22-26, 1963, during which we recorded our latest 80-degree day ever in town (the 23rd).

One other such streak that is worthy of note, though it does not qualify for this distinction, is the 21-consecutive days above 72 degrees that ended on Oct. 17, 1878 — meaning there was an October that had 17 straight days above 72.

The coming week will also have some really nice days, so our collective sense of the fine weather this fall will surely continue for most of this week.

Inevitably, however, winter will either creep in or rush in to replace these golden days of late fall. As that happens, try to find solace in the fact that we have just experienced a record-breaking streak of benign weather.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.