On Friday, the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison celebrated its 75th anniversary.

When the department was founded in June 1948, the modern science of meteorology was arguably just a few years old, and even basic understanding of the nature of the mid-latitude cyclones that batter us from October to May was truly in its infant stages.

The scholarship within our department over this three-quarters of a century has made enormous contributions to our science and, in turn, to the protection of lives and property through improved forecasts of both tropical and mid-latitude cyclones.

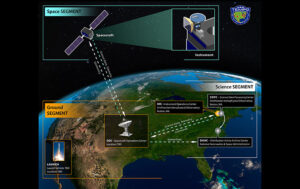

Some of the highlights include the launching of the first weather satellites in the late 1950s and early 1960s. These tools now contribute a huge amount of data to global weather forecasting models, and the UW-Madison remains at the very forefront of the research efforts dedicated to remotely sensing the atmosphere and oceans of Earth.

Developments in the computer models that make such forecasts also has a strong Wisconsin pedigree. The recently retired director of the National Weather Service got all three of his degrees from UW-Madison. The Space Science and Engineering Center, or SSEC, originally developed as an outgrowth of the department, has been at the heart of improved forecasts of tropical weather systems, fire detection and severe storms research for decades.

Clearer understanding of both tropical and extra-tropical weather systems, the global oceans and their interactions with sea ice, the complex climate system and many other important, fundamental issues in the atmospheric and oceanic sciences are being generated every day in our dynamic and diverse department. We are grateful to the citizens of the state of Wisconsin for their support of our endeavors, and those of all of our colleagues at our great University of Wisconsin-Madison.

On, Wisconsin!

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UWMadison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec. wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.