The spring equinox marks the beginning of the spring season in the Northern Hemisphere. Also called the vernal equinox, it is the time of year when the sun rises due east and sets due west, no matter where you live. Earth’s axis of spin is tilted at an angle of 23.5 degrees from its orbital plane and always points to the North Star. The orientation of Earth’s axis with respect to the sun changes throughout the year and is the fundamental cause of our seasons.

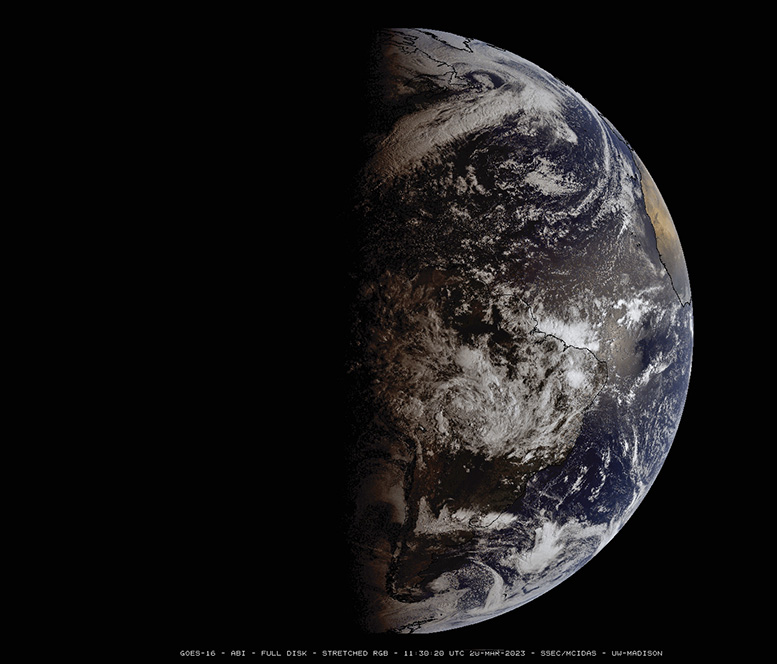

On the equinoxes, the axis is not pointed at or away from the sun. This results in all areas on Earth experiencing 12 hours of direct sunlight. On the equinox and at the equator, the sun appears directly overhead at noon.

The equinoxes occur when the sun’s rays strike the equator at noon at an angle of 90 degrees. During the spring and fall equinoxes, the sun is above the horizon for all locations on Earth for 12 hours. During the vernal equinox, the sun is moving from south to north as it crosses above the equator.

For a long time, people have marked the changing of seasons and the sun’s track across our skies. Stonehenge was constructed in a way that marks its relation to the Sun’s position in the sky and in different seasons. At Machu Picchu, stones mark the four cardinal directions so that exactly at noon on the equinox, no shadow is cast. In Chaco Canyon, the ancestral Puebloan people carved spiral designs into rock that track the seasons.

The sun crosses the equator today at 4:24 p.m. Central Daylight Time, a good time to go outside and celebrate the event.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.