A gale is a strong, sustained wind with wind speeds between 39 mph and 54 mph. The word is typically used as a descriptor for maritime weather.

The National Weather Service issues gale warnings when winds of this strength are expected for maritime settings. Gale warnings allow mariners to take precautionary actions to ensure their safety or to seek safe shelter. A gale warning flag is solid red and in the shape of an isosceles triangle. The equivalent warning for land is a wind advisory. The next level of warning for maritime winds that NWS issues is a storm warning for winds of 55-72 mph at sea.

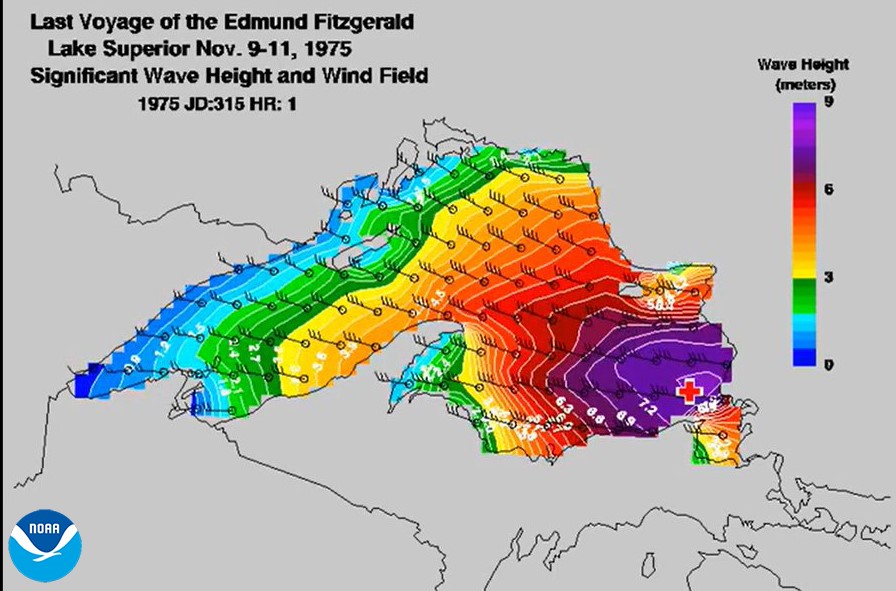

Gale winds are common in November on the Great Lakes. Last week saw the anniversaries of some strong November gales in the Great Lakes region. The most famous of these include the White Hurricane (Nov. 7-10, 1913), the Armistice Day Blizzard (Nov. 11, 1940), the Edmund Fitzgerald storm (Nov. 9-10, 1975), and the Nov. 10-11, 1998, storm.

The 1913 storm sank 19 ships and killed more than 250 people. Most of the damage occurred in Lake Huron.

The Armistice Day Blizzard dropped 16.7 inches of snow in Minneapolis/St. Paul. The cyclone intensified rapidly and was accompanied by a very intense surface cold front that quickly dropped the temperatures as much as 50 degrees in parts of the Midwest. This rapid drop in temperature caught many people by surprise, and more than 150 people perished.

The Edmund Fitzgerald storm achieved grisly fame through its association with the sinking of the ore freighter and the loss of its 29 crew members.

That storm also was accompanied by extremely strong winds and rapid intensification over the mid-continent.

That event was memorialized by Gordon Lightfoot’s ballad “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.”

The November 10-11 storm from 1998 saw a six-hour period during which its minimum sea-level pressure dropped 15 millibars.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.