Each winter we keep track of the areal extent of air colder than 23 degrees Fahrenheit at the 850 mb pressure level (about 1 mile above sea-level) around the entire Northern Hemisphere. This measure allows us to characterize the intensity of the winter season with respect to the lower tropospheric temperature.

Over the past 75 seasons there has been a systematic decrease in the December-January-February, or DJF, average areal extent of about 4.6%, and this is an unequivocal sign of global warming, measured in the winter season.

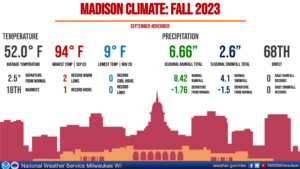

Another interesting aspect of this observational record arises from examining the buildup of the cold air leading into the winter. So, we have also kept track of the areal extent of such air from Sept. 1 to Nov. 30, SON, over the same 75 seasons. This year’s entry into that time series turns out to have been the sixth-warmest of all time — that is, it had the sixth-smallest areal average for SON.

A warm SON by this measure does not always mean a warm DJF in the following season. In fact, if one ranks the 75 SON seasons from warmest to coldest and then ranks the DJF seasons from warmest to coldest, there are years in which a warm SON is followed by a cold DJF and vice versa. Such years would be characterized by what could be termed a large “rank shift” — that is the ranking in one list is very different from the ranking in the other for the same season.

The largest rank shift in which the winter was colder than the fall occurred in 2002-03, when the fall was the 18th-warmest but the following winter was only the 58th-warmest, a rank shift of 39 places. Close on its heels but in the other direction was 2011-12, in which the fall was cold (70th-warmest) and was followed by the 17th-warmest DJF of all time — a rank shift of 53 places.

Current research is investigating whether or not there are systematic signs of a circulation change across the hemisphere that might give an early indication of whether or not a given year may experience such a dramatic change from fall to winter.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.