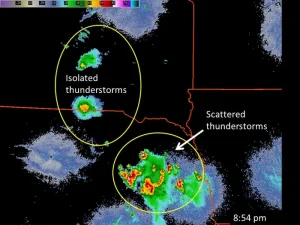

A tornado is a powerful column of winds that rotate around a center of low pressure. The winds inside a tornado spiral inward and upward, often exceeding speeds of 300 mph. Tornadoes form in atmospheres that have extremely unstable moist air, large amounts of vertical wind shear and weather systems, such as fronts or thunderstorms, that force air upward.

The continental United States provides these three ingredients in abundance.

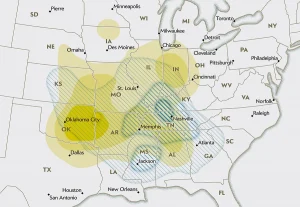

A plot of tornado tracks in the contiguous U.S. from 1990 through 2011 reveals a relatively high frequency in the central Great Plains. Texas to Kansas stands out as a region of high tornado occurrence. Tornado Alley traditionally refers to this region known for frequent tornadoes. It is a colloquial term, and there are no explicit boundaries to Tornado Alley.

A recent study found the corridor where many tornadoes in the U.S. occur has changed in recent decades. There appears to be an eastward shift of tornado activity, with a corridor that encompasses the states of Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia.

The published study analyzed tornado tracks that spanned two 35-year periods, one from 1951 to 1985 and the second from 1986 to 2010. In the first 35-year span tornado formations peaked in northern Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas — the area traditionally known as Tornado Alley. From 1986 to 2020 the most active tornado corridor shifted eastward, peaking in Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama.

Within the United States, tornadoes can occur in nearly every state and in every month of the year. When considering tornado activity, meteorologists focus on the specific conditions conducive to their formation: warm, moist, unstable air, and changes in wind speed and direction with height, rather than a fixed geographical area.

The scientific study also demonstrated that there are more winter tornadoes than in past decades. Wisconsin had its first tornado in February this year.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at noon the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.