“The Old Farmer’s Almanac” recently published its 2024-25 winter forecast. For the Upper Midwest region, it predicts winter will not be as cold as usual. The precipitation and snowfall forecast are for below average.

But don’t count on that forecast, as there is no proven skill. “The Old Farmer’s Almanac” does not share how it makes its forecast, so it cannot be judged scientifically. “The Old Farmer’s Almanac” also makes a weather forecast for specific time periods in a given season. Such detailed forecasts can be announced but are not trustworthy scientifically.

Seasonal weather forecasting is a science challenge. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center also makes seasonal forecasts. It explains the underlying principles of its forecast and provides validation of the forecasts publicly (see https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/long_range).

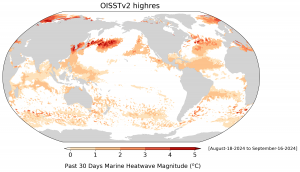

These modern day seasonal forecasts rely on known relationships between climate and some key forcing mechanisms, such as the El Niño. An El Niño is a periodic warming of the equatorial Pacific Ocean between South America and the international date line. This warming is a natural variation of the ocean and is used to predict departures from average conditions rather than to make specific weather forecasts. For example, a year with a strong El Niño leads to less snowfall than average in Wisconsin. These seasonal forecasts also take into account the climatic impacts of other global oscillations uncovered by the research of atmospheric scientists.

El Niño Southern Oscillation-neutral conditions are present, as equatorial sea surface temperatures are near to below average in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean. A La Niña watch is in effect, as La Niña is favored to emerge in September-November (71% chance) and is expected to persist through January-March 2025. Wisconsin winters tend to have more precipitation and near-average temperatures during a typical La Niña.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at noon the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc. edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.