A waterspout is a whirlwind that forms beneath a cumulus cloud over water. Before you see the waterspout, you may see a funnel-like cloud hanging from the cloud base. The Florida Keys, Gulf of Mexico, and Chesapeake Bay are common regions for waterspouts.

The Great Lakes also have waterspouts, though seasonally. August and September are the most common months for Great Lakes waterspouts to develop, with the full season considered to run from the end of July into October.

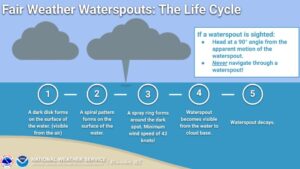

There are two types of waterspouts: fair weather waterspouts and tornadic waterspouts associated with severe thunderstorms. The fair weather variety of waterspout is more common than the tornadic and is the most common over the Great Lakes. A fair-weather waterspout is a whirlwind that forms beneath a cumulus cloud and over water and is generally not associated with thunderstorms. A fair weather waterspout develops on the surface of the water and moves upward.

Fair weather waterspouts form when cold air moves across warm water. They form when a large temperature difference between the warm water and the overriding cold air exists. Fair weather waterspouts develop in light wind conditions, so they tend to stay in one place or move slowly. They typically have weak circulations and winds, although the bigger spouts can produce wind gusts that can exceed 50 mph and can flip a small boat or damage a dock if they come ashore. Fortunately, these types of waterspouts move relatively slowly and are most often visible from a great distance over the flat expanse of lake waters, so there is ample time to get out of their way.

The International Centre for Waterspout Research is an international organization that monitors and studies waterspouts from all over the globe.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.