Fires require something to burn plus air to supply oxygen and a heat source to get the fuel to its ignition temperature.

Once a fire starts, weather is one factor of how it will spread and if it will grow. The important weather factors are temperature, wind and humidity. Warmer temperatures allow fuels to ignite quickly, and low humidity keeps the fuel dry and easy to burn. Wind brings oxygen to the fire and also can help to spread it.

A large fire can generate a wind pattern of its own that can help to spread the fire. Heated air near the ground is constantly and quickly rising in a large fire. As the air near the ground moves upwards, air from all around the fire rushes in towards the rising column of air. This movement creates an updraft.

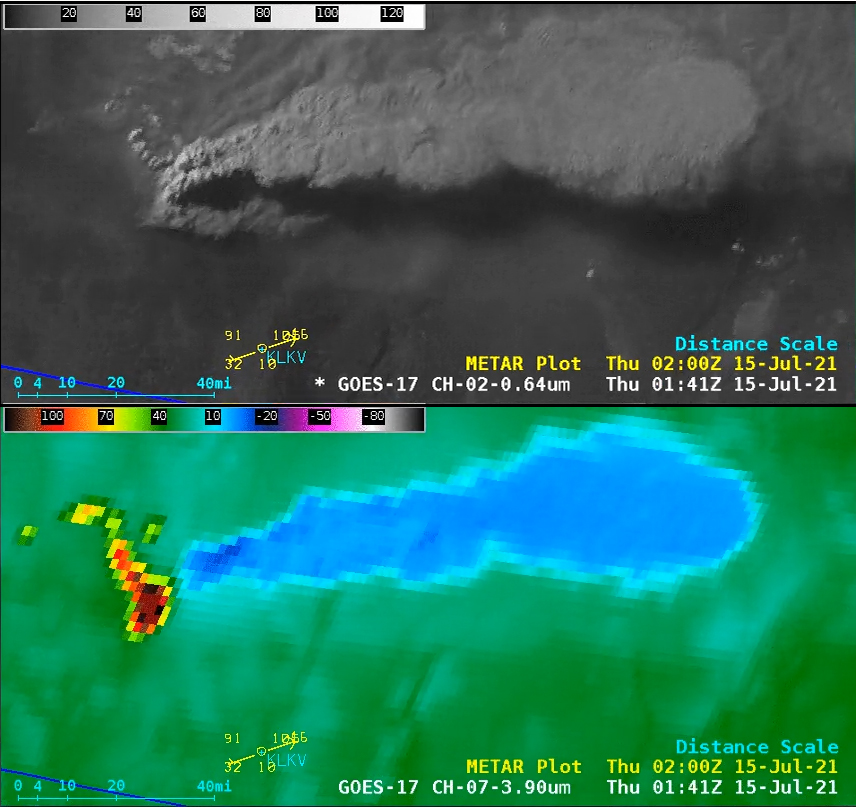

A large, hot fire can form a pyrocumulonimbus, or a “fire storm cloud.” These are much like thunderstorms. Pyrocumulonimbus can produce lightning, which could set off new fires. They also generate stronger winds that fan the fire, making it hotter and helping it to spread.

Rotating winds can develop along the edge of a hot fire, a result of the contrast between the hot air associated with the fire edge and the cooler air over the adjacent, non-burning region.

There is a wide range in the properties of a fire tornado, but they are usually 30 to 200 feet tall and about 10 feet wide. The largest fire vortices are associated with wildfires.

Fire tornadoes can be generated when the vortices are tilted from the horizontal to a vertical direction. Fire tornadoes can be composed of flames or black smoke and can toss burning debris into the non-burning area, helping to spread the fire.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.