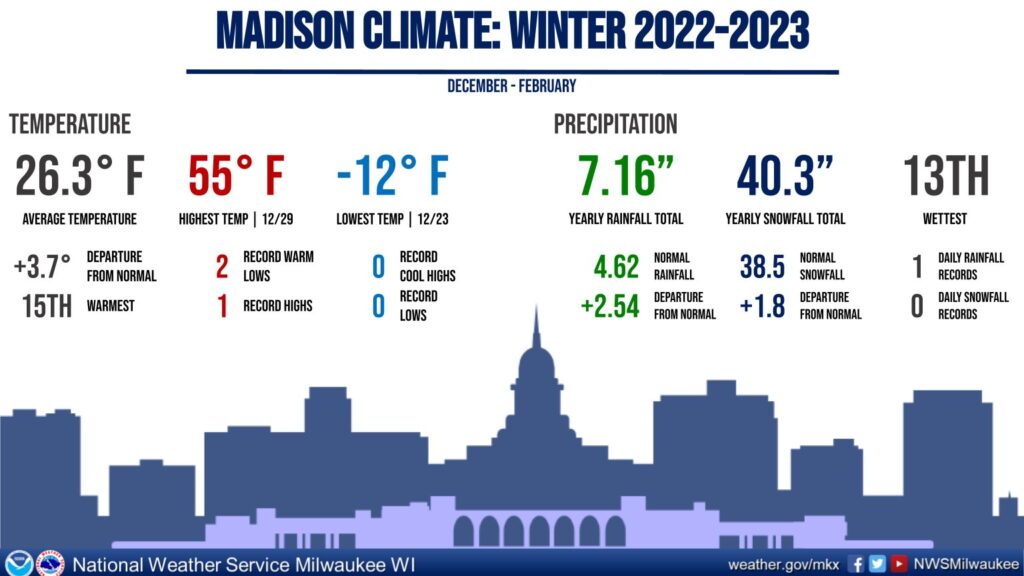

Meteorological winter in the Northern Hemisphere is often defined as the three months of December, January and February. The just-ended winter of 2022-23 was notable in a number of ways.

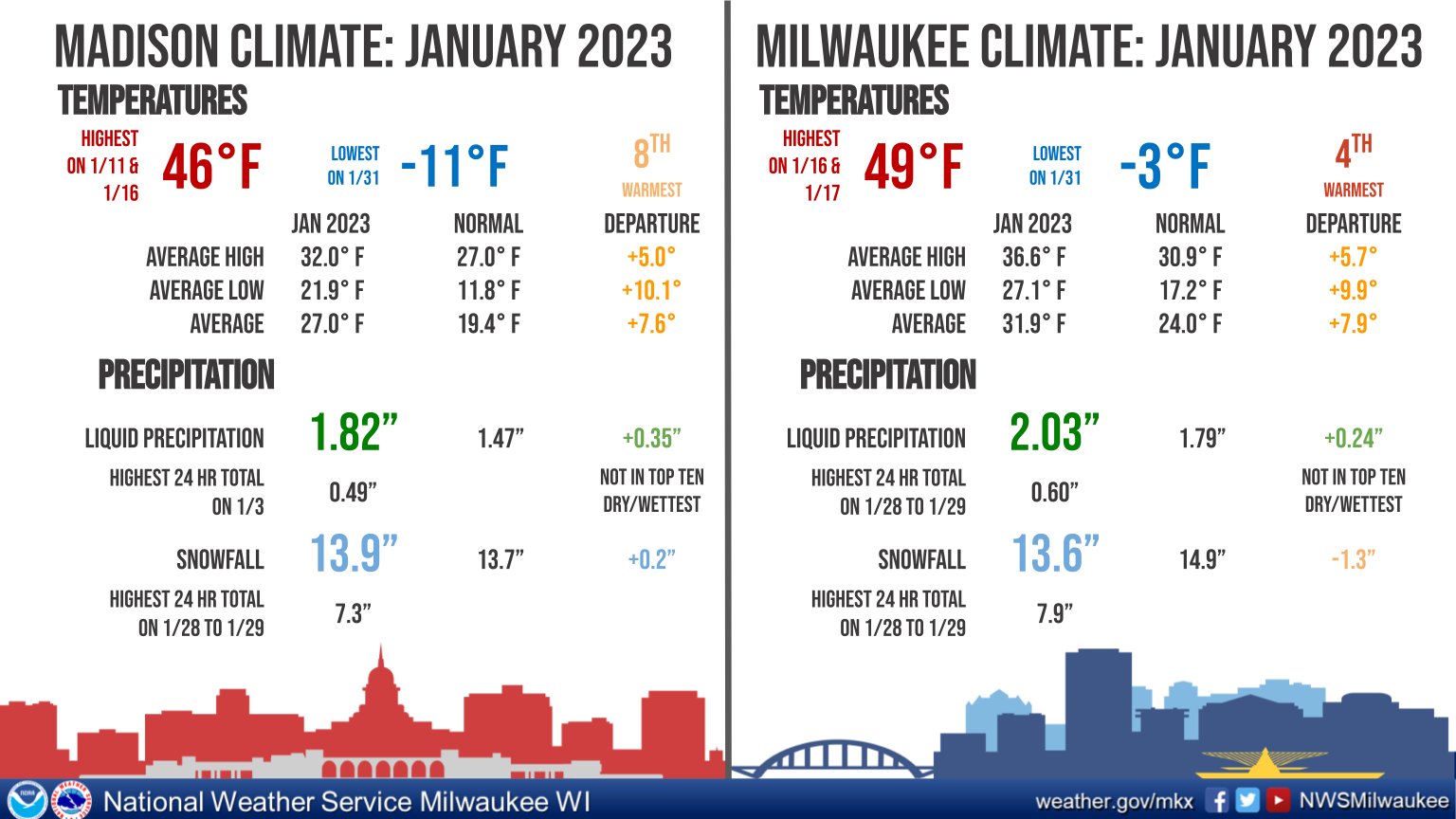

First, here in Madison we started with a chilly month of December during which we averaged 0.8 degrees below normal. This was also the only month of the season in which we had a day with a high temperature below zero — minus 3 on Dec. 23.

January was 7.6 degrees above normal and was followed by a February that was 4.4 degrees above normal. Thus, overall, December, January and February were 3.71 degrees above normal in Madison this winter.

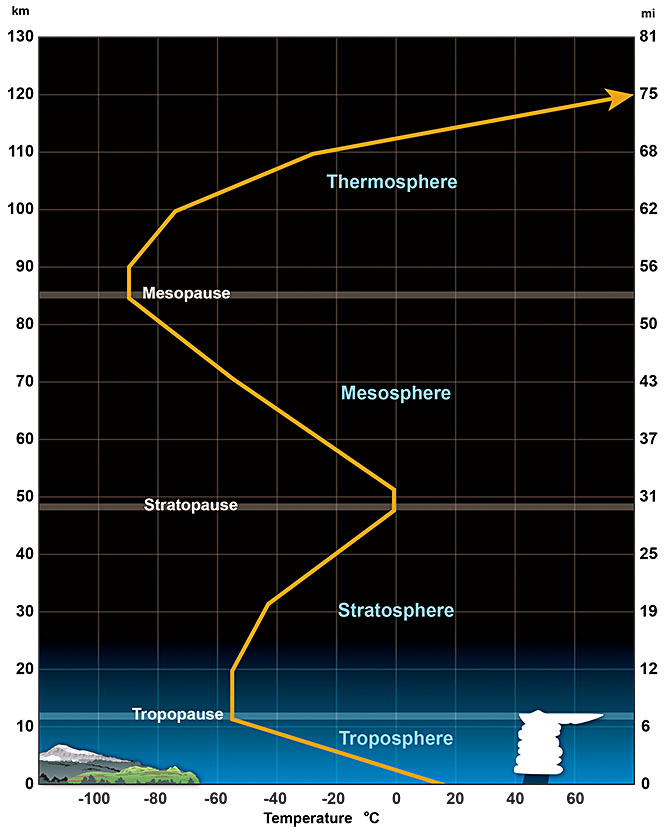

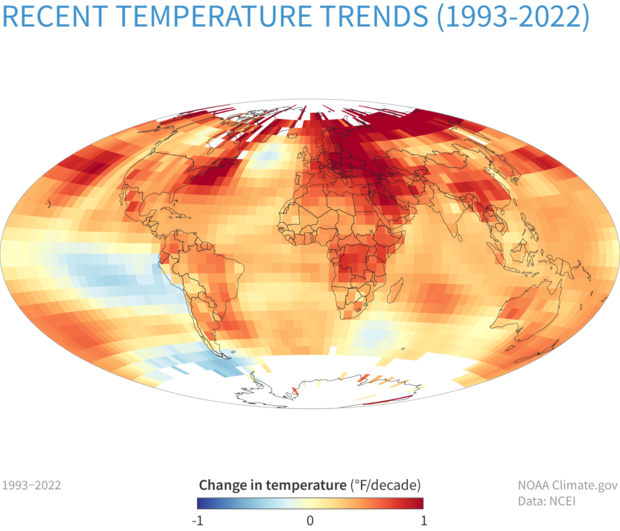

On the hemispheric scale, we can measure the areal extent of air colder than minus 5 degrees Celsius — 23 degrees Fahrenheit — at about 1 mile above sea-level (formally, at a level where the atmospheric pressure is 850 millibars) with records back to 1948-49. This year turned out to have the 16th smallest average areal extent over December, January and February — thus, by this measure, it was the 16th warmest winter in the last 75 years.

In fact, of the top 20 warmest winters measured this way, 17 have come since 2000-01. This is not a weird coincidence but instead is part of a longer trend that unequivocally reveals a slow but systematic warming of the planet. It is well past time that we as a society stop arguing about what is now settled fact — that global warming is real and ongoing — and start spending our collective intellectual energy on deciding how best to confront this reality.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.