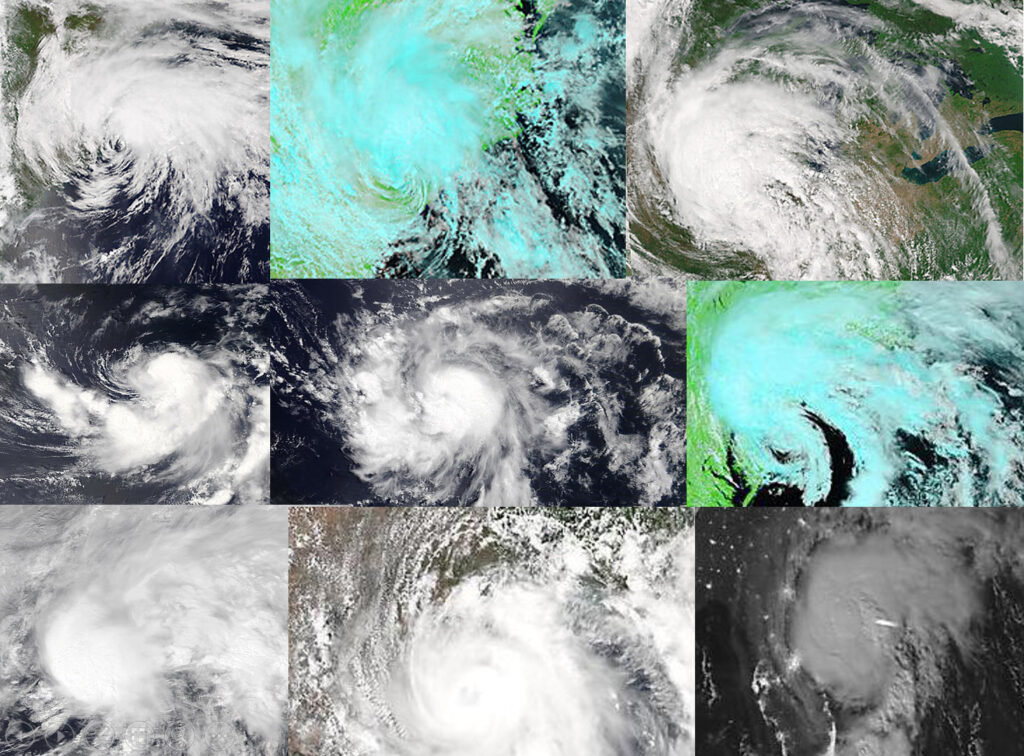

The Atlantic basin hurricane season is off to a roaring start in 2020.

Credit: CIMSS, SSEC and NASA

The official season stretches from June 1 through Nov. 30. One measure of the activity of a season is the number of named storms — those that reach or exceed sustained winds of 39 mph — that season accrues.

This year, for the sixth year in a row, Atlantic tropical storms formed before the official start of the season with Arthur and Bertha developing in May.

NOAA had predicted an abnormally active hurricane season this year with as many as 19 named storms, with three to six of them likely to develop into fearsome Category 3, 4 or 5 storms.

With the development of Hurricane Isaias on Friday, we are already at nine for the season as we are just about to enter the most active part of it. An average hurricane season in the Atlantic produces 12 named storms with about six of those becoming hurricanes.

Among the most important considerations regarding these storms is how many of them will strike land and where — nearly impossible to predict on the seasonal time scale.

Certainly, a higher number of total storms would suggest a greater chance of at least one of them making a major landfall so an abnormal frequency is of concern.

Recent years make this point well. The 2010 Atlantic season had 19 named storms, the third most of any season since 1851. However, only one storm, and only at tropical storm strength, made landfall in the U.S. that year.

In contrast, the 1992 season had only seven named storms but one of those was Hurricane Andrew which devastated south Florida as one of only four Category 5 storms to ever make landfall in the US.