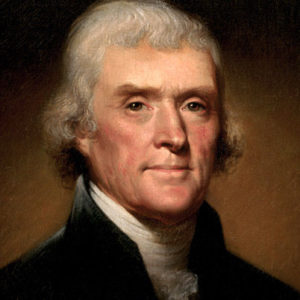

Thomas Jefferson, author of our Declaration of Independence and an avid weather observer, recorded a mild summer day with a high temperature of 76 degrees as we declared independence from Britain on July 4, 1776. (Official Presidential portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale, 1800)

July was the month of revolution in both America and France in the late 18th century as we declared independence from Britain on July 4, 1776, and the French Revolution began with the assault on the Bastille in Paris on July 14, 1789. It is interesting to examine the extent to which weather may have influenced the passions that led to these seismic events.

The author of our Declaration, Thomas Jefferson, was such an avid weather observer that he brought his instruments with him from Monticello to Philadelphia that summer. He recorded a mild day on July 4 with a high temperature of 76 degrees. Phineas Pemberton, a prominent citizen, independently recorded the same high temperature – nearly 10 degrees Fahrenheit below normal. Pemberton also noted a wind shift from northerly to southwesterly with a falling pressure as often accompanies passage of a surface high-pressure system. Thus, the great revolutionary act in America was birthed in benevolent weather conditions.

Not so for the French Revolution. The summer of 1788 had been exceptionally dry across the country and led to widespread crop failure. The hot, dry summer was followed by an unusually cold winter that made keeping warm more expensive. Food shortages brought on by the prior summer’s drought intensified in the spring of 1789 and left the populace, already frustrated with the opulence of Versailles, in a heightened state of agitation. Recent analysis by scholars at the London School of Economics has suggested that these conditions were a proximate cause to the civil unrest that led a mob of Parisians to storm the Bastille and, effectively, ignite the French Revolution.