Yes. Radar, an acronym for RAdio Detection And Ranging, consists of a transmitter and a receiver. The transmitter emits radio wave pulses outward in a circular pattern. Objects scatter these radio waves, sending some energy back to the transmitting point where it is detected by the radar’s receiver. The intensity of this received signal indicates the size and density of the suspended objects, such as precipitation. The time it takes for the radio wave to leave the radar and return indicates the distance.

Radar is designed to detect precipitation intensity and type, but it can detect living things as well. Flying insects in huge numbers can reflect enough energy back to a radar site to be detected. As an example, mayflies emerge in summer in enormous numbers around the Mississippi River between Wisconsin and Minnesota and are often detected by the weather radar in La Crosse, WI.

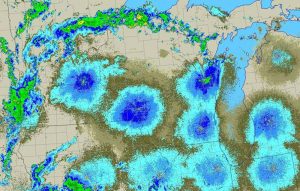

Some bird species gather at large communal roosting sites, particularly during their migration. The birds can be seen on radar as a flock takes off in the early morning. The flock appears on radar as an expanding, fading ring until they either fly above or below the radar beam and are no longer detected. Their signature often appears on radar during the morning departure, but not in the evening when they return. This is because atmospheric conditions affect the radar beam path. The beam is bent slightly downward in early morning due to a temperature inversion that often develops in the lower atmosphere. This departure in the path allows the radar to detect objects at lower altitudes more easily. During the evening, temperature inversions are weaker or non-existent and the beam bending doesn’t occur, inhibiting detection.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at noon the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc. edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.