Hurricanes are large-scale, organized storms that form in the tropical latitudes.

They are fueled by the enormous amount of heat released when water vapor, evaporated off the warm tropical ocean surface, changes phase to liquid and ice in the thunderstorm clouds of the hurricane.

They are smaller in areal extent than the storms that commonly affect us in the mid-latitudes here in Madison.

The distribution of clouds and precipitation in a hurricane is usually symmetric about its center (the eye). This is vastly different from the characteristically asymmetric distribution of clouds in our more familiar extratropical cyclones.

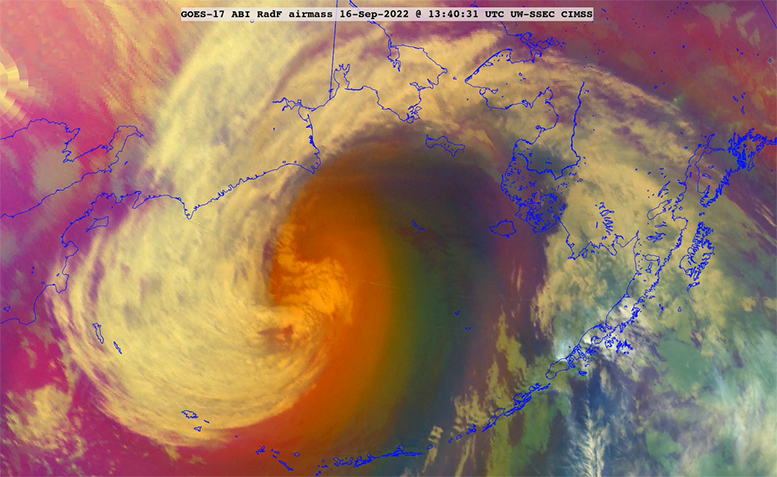

Despite their tropical origin, hurricanes do find their way to the mid-latitudes with regularity, especially in the western Pacific Ocean basin. When they make this excursion they often undergo a dramatic restructuring that, in concert with interactions from the wavy flow of the mid-latitudes, can lead to powerful extratropical storms.

Such a situation occurred on Friday and Saturday when former Typhoon Merbok migrated from the tropics toward the central Bering Sea and became a devastating extratropical cyclone with 50 foot seas and wind gusts exceeding 80 mph.

Such extratropical transitions are most frequent in September and October in the Northern Hemisphere and can have global ramifications for the weather and its predictability. In the present case, there is a very good chance that extreme rainfall in central California in the middle of this week may be one result of Merbok’s dramatic conversion.

Steve Ackerman and Jonathan Martin, professors in the UW-Madison department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, are guests on WHA radio (970 AM) at 11:45 a.m. the last Monday of each month. Send them your questions at stevea@ssec.wisc.edu or jemarti1@wisc.edu.