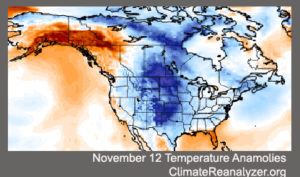

Almost no one in the Midwest will be unaffected by the remarkable cold air outbreak that occurred over the past weekend.

And if you think that we were paid a rather early visit by such air this year, you are right.

A vigorous cold air outbreak such as we just experienced is usually a midwinter, not late fall, phenomenon.

As with most unusual events in the atmosphere, this cold air outbreak was a commingling of circumstances — some common and some not — brought to extreme by perfect timing.

Because the sun has long since set for the winter at the North Pole, the endless night is a breeding ground for very cold air masses. As we head into mid-November, the darkness has crept southward into northern Canada bringing with it an even more proximate source of very cold air. That circumstance is the same every year.

The high altitude flow of air around the hemisphere is most often predominantly west to east. Occasionally, large north-south meanders develop in this flow, bringing warm tropical air toward the pole in the northward directed flow and cold, polar air toward the equator in the southward directed flow.

Late last week a strong ridge of high pressure developed at high altitude over the west coast of the United States and Canada. The eastern side of such a ridge is characterized by southward flow which, in this case, ushered a mass of cold air from high latitude central Canada into the central United States while simultaneously providing support for the strong offshore flow across California that supported the devastating fires in that state.