Our rainy Friday was arguably the first storm, or cyclone, of the autumn/winter season. Though it will surely be followed by more powerful examples, you may well have wondered how do such storms come to be?

That has been the central motivating question in meteorological science for most of the past 100 years. During that time, meteorologists have learned a great deal about how these mid-latitude cyclones are formed.

In most instances, two or more days before the storm is noticed at the surface of the Earth, processes are at work in the upper troposphere. Specifically, at the height of the jet stream (about 6 miles above the surface), weak downward vertical motions begin to drag the tropopause downward into the middle troposphere. This process eventually results in the creation of a mid-level vortex, a region of counterclockwise-rotating winds, about 3 miles above the ground.

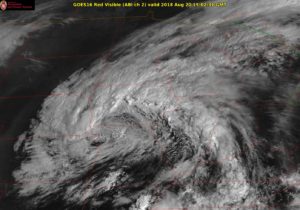

Once generated, this vortex is then moved around by the atmospheric winds in its vicinity. At the forward side of this moving vortex, the air is forced to rise. Such upward vertical motion evacuates air from the lower troposphere, lowering the pressure at the surface.

Simultaneously, the upward vertical motion produces clouds and precipitation. So long as the mid-level vortex continues to intensify and move, so too does the surface cyclone. In many cases, the mid-level vortex eventually becomes quasi-stationary and positioned directly above the surface cyclone. This usually marks the end of the intensification for the storm though it can still deliver high-impact weather at this stage.